Welcome to another issue of Plain Great Stuff, a newsletter/blog where I tell you about (often weird) things and why I like them.

I recently thought I had a brilliant idea for a utopian alternative history story: What if radical abolitionist John Brown’s 1859 raid on Harpers Ferry hadn’t failed? What if instead of just being a spiritual catalyst for a Civil War, he was the direct military catalyst—helping lead an organized guerilla campaign of armed freed people to create a more just America than the one we live in now?

But it turns out Hugo and Nebula-award winning author Terry Bisson had the idea first—and published a book about it a year before I was born.

Bisson’s 1988 novel Fire On The Mountain is a masterful piece of alternative history fiction, one that weaves timelines to allow the reader to bear witness not only to the successful insurrection, but also the Marxist Afro-future that results. (Kudos to my friend Renée for pointing me in its direction as soon as I tried to pitch her my version.)

And Bisson was gracious enough to talk via phone with me about how the book was inspired by his own involvement and admiration for leftist movements as well as Brown’s enduring legacy in our cultural memory.

But before digging in too deep, I’ll take a step back here an introduce Brown—since I know not everyone grew up surrounded by his mythos. In my home state of Kansas, Brown literally looms over our origin myth: He stands above Kansas free soilers and Missouri border ruffians battling on the prairie, Tornado at his back, in John Steuart Curry’s Tragic Prelude mural in the State Capitol. (Seen at the top of this post.)

The modern state of Kansas was born out of the blood of abolitionists who settled stolen land in an attempt to at least stop the spread of slavery further west, in a conflict known as the Border War or Bleeding Kansas. But Brown was more radical than most, advocating for a militant response to the injustice of slavery.

He led an attack on a pro-slavery settlers in 1856 generally known as the “Pottawatomie Massacre,” taking revenge for the sacking of freestate stronghold Lawrence (where I went to college) and the nearly fatal caning of Massachusetts abolitionist Senator Charles Sumner by pro-slavery opponents on the Congressional floor by executing several men. Skirmishes continued on what was then the frontier and Brown carried on underground: A hero celebrated as “Captain Brown” by those ultimately on the right side of history, but living essentially the life of a fugitive terrorist until he was captured and executed for treason after the failed Harpers Ferry raid.

That raid was his most daring maneuver yet: an attack on a federal arsena at a strategic choke-point in what was then Virginia—attempting to spur a second American Revolution to end slavery and rebirth the nation while relying on the tenets of racial equality laid out in a Constitution drafted at the 1858 Chatham Convention in Canada.

It failed, and most who participated died during the fighting or were executed afterwards — including Brown, who was hanged on December 2, 1859.

Yet in death, Brown lived on as a martyr—and the central figure of the Union marching tune “John Brown’s Body,” which makes a Philip K. Dick-esque cameo in Bisson’s novel which I won’t spoil further.

The Fire On The Mountain was influenced, the author told me, by his own involvement at the time with the John Brown Anti-Klan Committee, part of the anti-racist movement that evolved out the New Left. That work, along with trips to places connected with Brown including visiting a friend in Lawrence and many drives down the Blue Ridge mountains to visit family in the south, where Bisson and his wife are from, while the pair lived in New York led Bisson to dig into Brown’s story and imagine a world where he won.

Bisson credits much of the revived public interest and scholarly re-interpretation of Brown with radical civil rights movements of the 1960’s and 70’s, which he was just a little too young to fully participate in.

“John Brown was considered kind of a nut for many years, he was vilified in American history,” he said. “One of the things the Weather Underground did was change that,” Bisson added, noting that they group named their current events magazine Osawatomie—one of many nicknames Brown, derived from the site of a Bleeding Kansas battle where one of his sons who also joined the anti-slavery cause was killed.

My decade of escaping my adopted hometown of Washington, DC to the mountains of Virginia and West Virginia certainly taught me that even today Brown’s legacy is debated and colored by Lost Cause revisionism. Those visiting the John Brown Wax Museum in Harpers Ferry, West Virginia—where he is essentially hanged in effigy—get a much different version of his story than the people who visit the preserved Brown family cabin in Osawatomie, Kansas.

That is, of course, the way stories—including history—goes: everyone gets their own interpretation. But one of the powerful things for me about the practice of history and re-examining it through science fiction forms like alternative histories is thinking critically about stories we perpetuate and who gets to star in them.

In Fire On The Mountain, as Bisson and I discussed, Brown isn’t really a character in the book: he’s central to the narrative, but largely referenced at a distance—looming over the story much like he looms over the plains in the Tragic Prelude.

Another alternative

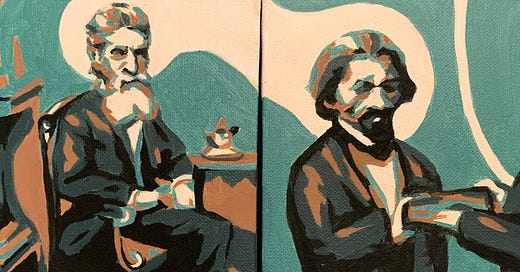

Expect much more from me, with the help of Bisson and others, on the topic of alternative histories soon. But in the meantime, please enjoy the portrait studies above I made after my conversation with Bisson, featuring John Brown and Frederick Douglass as though they were inaugurated president in 1861 and 1865 respectively. (This is not spoiler of how things go down in the book—it reflects how the timeline would have played out in narrative I was starting to outline when I discovered Bisson’s epic…)

The left mashes together a late-era photo of Brown with the first photograph of Abraham Lincoln post inauguration and the right combines a newspaper sketch of Andrew Johnson’s inauguration with a contemporary photo of Douglass.

You can also expect more about whose stories we choose to tell later, which I’m previewing below by sharing portraits of two often over-looked black abolitionist leaders: Osborne Perry Anderson and Mary Ann Shadd Cary. Anderson was the sole back survivor of Brown’s raiding party on Harper’s Ferry, who published a first hand account of his participation in 1861—with the help of Shadd Cary, herself an abolitionist and pioneering black female publisher and lawyer.

What else is great?

Well, related to this week’s newsletter:

Obviously check out Fire On The Mountain by Terry Bisson. I’m also eager to jump into his novel Any Day Now, which promises to explore another alternative America set in the radical 1960’s.

Bleeding Kansas: Contested Liberty in the Civil War Era by Nicole Etcheson is a great study of the birth of the Sunflower State.

Read Osborne Perry Anderson’s first-hand account of how the raid actually happened: A Voice From Harper’s Ferry as well as Eugene Meyer’s book Five For Freedom to learn more about Anderson and the other black men who took up arms with Brown at Harpers Ferry, plus check out the New York Times 2018 “Overlooked No More” obituary of Mary Ann Shadd Cary.

Learn just how close Frederick Douglass may have been to joining Brown in taking up arms in Theodore Hamm’s Jacobin article “When Frederick Douglass Met John Brown.”

The Field of Blood: Violence in Congress and the Road to Civil War by Joanne Freeman is an eye-opening look at just how uncivil Washington, DC was while fighting was breaking out in Kansas.

Otherwise, I’m skipping a Cursed Monkey’s Paw recommendations this week, but heartily suggest the just released Gangstagrass single Nickel And Dime Blues as a soundtrack for our current times: Gangstagrass mixes together rap and bluegrass traditions to make an irresistible musical cocktail and their latest song somehow makes even being broke during the pandemic sound like it’s worth dancing about.

Per Glide Magazine, we can expect a whole new Gangstagrass album called No Time For Enemies that “grapples with the dual crises of race relations and politics in modern day America” in July. Sounds like music we need right now.

Pets, Plants, and Partings

We’re actually briefly away from our precious purr-children this week, but are so grateful to friend (and newsletter subscriber) Kerry for checking in and sending updates about (our apparently very hungry) boys.

As for the irises…

… still going strong, though some are so top heavy they’ve fallen over.

Special thanks this week to John Brown, who was born 220 years ago this past Saturday, as well as Terry Bisson, who responded almost immediately when I pinged him to talk about our mutual interests—plus subscriber Stephen Fehr for sharing his own iris bounty with me on Twitter.

See you next week! Until then, you can find me on Twitter as @kansasalps or at my website Plain Great Productions.

Stumble upon this by accident or get it sent as a forward and want the next issue in your inbox? Sign up below.